How Much Excess Mortality Can Science Definitively Attribute to SARS-CoV-2?

Michael Postel M.S. Economics Rutgers University 2008

Abstract

Chinese virologists spent one week investigating the root cause of COVID-19 disease in Wuhan, China, a rather polluted city relative to the optimization of human health. One week of scientific investigation and the case was closed, the monocausal viral theory was here to stay. Questioning the dominant narrative anchored by such hasty conclusions is necessary and should be expected and even welcomed. The scientific community has an obligation to properly account for the potential cause of psychological distress and the absence of proper nursing home care on excess mortality before anything viral in nature can account for all the excess mortality experienced in the U.S. in 2020. This paper explores the causal tenets of the monocausal viral theory and attempts to examine the possibility that much of the excess mortality could be better explained by the sudden onset of psychological trauma coupled with the improper care in nursing homes throughout the U.S. in 2020.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, psychological distress, nursing home care, excess mortality

Introduction

In 2020 there was a dominant narrative disseminated to the American public regarding a novel, highly infectious, and pathogenic disease-causing virus that persists to the present. Specifically, there is a novel coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 that has caused an increase in a unique, severe, and deadly respiratory illness in the U.S. and around the world. On Dec 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) alerted the public that there was a group of forty-one patients suffering a suspiciously severe case of pneumonia in Wuhan, China (Neilson and Woodward, 2020). One week later, virologists asserted on January 7th that a novel coronavirus is to blame (Neilson and Woodward, 2020). Since the first week of January 2020, the mainstream media and the U.S. Government have not seriously entertained any alternative theories. One week of scientific investigation and the case was closed, the monocausal viral theory was here to stay.

Rest assured, scientific enquiry has no tolerance for laziness or stones left unturned. That is, there is nothing unscientific about questioning the mainstream hypothesis that there is a highly infectious and pathogenic virus rampaging the human population, quite the contrary. Questioning the dominant narrative anchored by such hasty conclusions is necessary and should be expected and even welcomed.

The Importance of Skepticism in Scientific Enquiry

In their cross disciplinary analysis of scientific principles, the National Research Council (2002) identify principles of scientific enquiry shared across disciplines such as “astrophysics, political science, and economics, as well as to more applied fields such as medicine, agriculture, and education. The principles emphasize objectivity, rigorous thinking, open-mindedness, and honest and thorough reporting” (p 52). In their discussion of contemporary scientific investigation, they identify the key tenets underpinning the culture of the modern scientific community.

The culture of science fosters objectivity through enforcement of the rules of its “form of life”—such as the need for replicability, the unfettered flow of constructive critique, the desirability of blind refereeing—as well as through concerted efforts to train new scientists in certain habits of mind. By habits of mind, we mean things such as a dedication to the primacy of evidence, to minimizing and accounting for biases that might affect the research process, and to disciplined, creative, and open-minded thinking. These habits, together with the watchfulness of the community as a whole, result in a cadre of investigators who can engage differing perspectives and explanations in their work and consider alternative paradigms. Perhaps above all, the communally enforced norms ensure as much as is humanly possible that individual scientists—while not necessarily happy about being proven wrong—are willing to open their work to criticism, assessment, and potential revision. (National Research Council, 2002, p 53)

The National Research Council (2002) suggests an important tenet of scientific culture is for scientists to be open to scrutiny and the possibility of being wrong. Thus, not only are asking questions, being skeptical, and analyzing dominant theories central and most important tenets of the scientific process, one might argue it is an obligation of the scientific community.

Virologists seem convinced that a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is the main causal factor explaining the excess mortality that occurred in the U.S. in 2020. However, the connection is unclear after reviewing the overarching data. The predominance of the asymptomatic carrier, for example, poses the first point of contention in the supposed causal connection. According to The COVID Tracking Project (2021), there were roughly 19.9M cumulative positive SARS-CoV-2 tests in the U.S. in 2020, but only approximately 686 thousand cumulative hospitalizations due to COVID-19. If over ninety-five percent of those who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 do not end up requiring hospitalization from the COVID-19 disease (The COVID Tracking Project, 2021), how are we so sure that a novel coronavirus is to blame? The supposed viral causal inference, not posited, but asserted by virologists does not fit as nicely as other causal inferences between the microscopic world of viruses and genetic material and naked-eye observable reality. For example, infant rats with Haemophilus influenzae bacteria developed documented Meningitis over seventy percent of the time (Moxon et al., 1974), as opposed to less than five percent of the time with SARS-CoV-2. Thus, virologists must take to the lab where they can tease out causality in a controlled environment.

According to several medical journals, virologists have successfully shown a causal connection between SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 disease. However, there clearly appears to be a cosmic entanglement of confounding causal connections between the electron-microscopic world of viruses and the naked-eye observable reality of human disease as evidenced by the inconsistent correlation between positivity rates and hospitalization and mortality rates. As Campbell et al. (2002) note, critics of scientific enquiry argue that “[…] undetected constant biases can result in flawed inferences about cause and its generalization. As a result, no experiment is ever fully certain, and extrascientific beliefs and preferences always have room to influence the many discretionary judgments involved in all scientific belief” (p. 28). This may be overly critical of the philosophies and principles underpinning the varied experimental scientific designs, but it does at least crack the door open to speculation of dominant narratives and the discussion of alternative explanations of mysterious phenomena, such as the COVID-19 disease.

Teasing Out Causality from Correlation

When teasing out causality, all researchers default to the same set of logical principles as laid out by John Stewart Mill. Mill provides three basic conditions that should be met when working to understand causal connections, as opposed to spurious correlations. According to Vogt (2011), they are as follows:

“When discussing [controlling for covariates], we still almost always begin with John Stewart Mill’s three conditions for causation. To conclude that two variables (call them A & B) are causally linked the researcher must demonstrate three things. First, the presumed cause (A) must precede the effect (B), since “after” cannot cause “before.” Second, the hypothesized cause and effect (A & B) must covary, because if they do not occur together, they cannot be causally linked. And, third, no other explanation accounts as well for the covariance of A & B, the postulated cause and effect. The last condition is the truly difficult one. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that all research methods concerned with causality are attempts to deal with it, that is, to improve the degree to which we can claim that no rival explanation better accounts for the one posited in the researcher’s theory.” (Vogt, 2011, p. xxix)

The problem with the mainstream narrative that a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is the singular cause of all the excess mortality in the U.S. in 2020 is that none of Mill’s three conditions for causation are satisfactorily met. Consider the first principle of causation: “the presumed cause (A) must precede the effect (B), since ‘after’ cannot cause ‘before’” (Vogt, 2011, p. xxix). In this case A is the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, and B represents the COVID-19 disease. It is not clear that SARS-CoV-2 consistently precedes the COVID-19 disease.

There is no complete taxonomy of mammalian viruses, and it would cost billions of dollars and many years to even approach such a goal (Anthony et al., 2013). There is no way to definitively assert that SARS-CoV-2 is new to planet earth, mammals, apes, or even great apes. According to Tom Jefferson, a senior associate tutor at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) at Oxford, the SARS-CoV-2 virus may have always been here.

I think the virus was already here — here meaning everywhere. We may be seeing a dormant virus that has been activated by environmental conditions. There was a case in the Falkland Islands in early February. Now where did that come from? There was a cruise ship that went from South Georgia to Buenos Aires, and the passengers were screened and then on day eight, when they started sailing towards the Weddell Sea, they got the first case. Was it in prepared food that was defrosted and activated? Strange things like this happened with Spanish Flu. In 1918, around 30 per cent of the population of Western Samoa died of Spanish Flu, and they hadn’t had any communication with the outside world. The explanation for this could only be that these agents don’t come or go anywhere. They are always here and something ignites them, maybe human density or environmental conditions, and this is what we should be looking for. (“Coronavirus Existed Everywhere,” 2020)

If the virus, SARS-CoV-2, has always been here, it alone clearly does not cause anything. There must be a significant chapter missing from the dominant monocausal viral hypothesis. While SARS-CoV-2 may play an important part in the COVID-19 disease, it is not clear that the virus is causing the disease. It is likely that the virus has expressed itself in response to some yet unknown agitation.

To go a step further, is it entirely possible that coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, are a natural and healthy part of the body’s virome and not a causal factor in the COVID-19 disease? The majority of people who test positive for the coronavirus do not end up requiring hospitalization and do not end up dead (The COVID Tracking Project, 2020). In fact most people who test positive exhibit no symptoms at all and are considered asymptomatic. If over ninety percent of positive test cases do not end up requiring hospitalization or end up dead, would it be illogical to wonder if SARS-CoV-2 is actually good for your immune system since most people who have it do not end up requiring hospitalization or dead? Our first principle of causation does not seem bullet proof at first glance.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus does not cause illness or disease in most people, especially young, healthy people. This does not mean Mill’s first principle of causation is dead in the water. Correlation does not assume causation. Any student of quantitative research methods will recognize the following two most common heuristic examples for misconstruing causation. First, an alien researcher observing humans on earth incorrectly assumes that firemen must be the cause of fires because every time the alien observes a fire, firemen are also present. Second, an ignorant observer finds that every time there is a dead body, there are maggots; thus, maggots must be the cause of death. Clearly, firemen do not cause fires, and maggots do not kill living organisms. They arrive after the fact, not before.

Consider the correlation between smoking and lung cancer. Most people who smoke cigarettes, for example, do not end up suffering from lung cancer, however, smoking does significantly increase your risk of developing lung cancer (Ridge et al., 2013). Can we say that the presence of SARS-CoV-2 significantly increases one’s risk of developing the COVID-19 disease? This question is difficult to answer given publicly available data, but the answer is probably yes. But even here we run into trouble teasing out causality.

Since most people who smoke do not end up developing lung cancer, it cannot be concluded that cigarette smoke directly causes lung cancer. It must be more complicated than that. Perhaps it is some carcinogenic byproduct of burning the tobacco leaf, or maybe it is the nicotine or pesticide residue from the tobacco leaf, or a consequence of the fillers and/or additives in a cigarette that are causing irreparable damage to the lungs that opens the door for cancer. So how do we know that a supposedly novel, infectious, and pathogenic virus appears first and then a respiratory disease occurs after? Can it also be true that some unknown agitator or toxin appears first, and then the virus expresses itself in our virome, and then disease follows? Sadly, there is no definitive proof that a virus occurs first and then disease follows.

According to Mill’s second principle of causation, A and B must covary. That is, the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, and the diagnoses of COVID-19 must consistently occur together. Let us again consider the relatively non-controversial and generally accepted causal connection between smoking and lung cancer. According to a 2013 study of the epidemiology of lung cancer, about “90% of male lung cancer deaths and 75%-80% of female lung cancer deaths in the United States each year are caused by smoking” (Ridge et al., 2013). That is, the overwhelming majority of people who have died from lung cancer in the U.S. were habitual smokers. Moreover, according to the CDC, “People who smoke cigarettes are 15 to 30 times more likely to get lung cancer or die from lung cancer than people who do not smoke” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). Can something similar be said about the novel coronavirus? Have the overwhelming majority of people who have died from pneumonia, influenza, or COVID-19 (PIC) in the U.S. in 2020 also tested positive for COVID-19? This is a difficult question to approach because of the varied nuances of respiratory diseases. Focusing on mortality associated with pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19 (PIC), the answer here is probably yes. That is, most people who died due to illness or disease associated with PIC in the U.S. in 2020 probably tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The question cannot definitively be answered with the publicly available data, but it seems likely given what data is available.

Given the 361,891 cumulative deaths strictly related to COVID-19 versus the 540,032 deaths related to pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19 (PIC), COVID-19 related deaths comprise roughly 67 percent of total PIC deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Based on the available data, it seems very likely that mortality due to COVID-19 (B) and the presence of SARS-CoV-2 (A) covary most of the time. However, the causality link is backwards because the converse is not true. That is, over ninety percent of people who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 do not end up suffering from COVID-19 disease.

Testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 does not necessarily increase your risk of developing COVID-19 as in the case with smoking and lung cancer; though this is difficult to definitively conclude given publicly available data. Given the 19,864,374 cumulative positive SARS-CoV-2 test results in the U.S. in 2020 versus the roughly 686,115 cumulative COVID-19 related hospitalizations in the U.S., just 3.5 percent of those who tested positive for COVID ended up requiring hospitalization (The COVID Tracking Project, 2020). Conversely, 96.5 percent of those who tested positive for COVID did not end up requiring hospitalization. Mill’s second condition for causation, that A and B must covary, is not clearly met the closer we look at the details surrounding the SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 connection.

Virologists discovered evidence of SARS-CoV-2 months in advance of the first diagnosed COVID-19 cases in several countries, including Spain, Italy, and the U.S. Where is the covariance between SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 during this time? Spanish virologists discovered the novel coronavirus in a sample of Barcelona wastewater nine months prior to the first COVID-19 case in China. “SARS-CoV-2 was detected in Barcelona sewage long before the declaration of the first COVID-19 case, indicating that the infection was present in the population before the first imported case was reported” (Chavarria-Miró et al., 2020). A similar discovery was also made in Italy. According to researchers, “A total of 15 positive samples were confirmed by both methods. The earliest dates back to 18 December 2019 in Milan and Turin and 29 January 2020 in Bologna” (La Rosa et al., 2021). Since SARS-CoV-2 does not consistently covary with COVID-19, it would seem illogical to conclude that A is causally connected to B. Furthermore, it seems extremely illogical to latch on to this monocausal viral theory and shut down all other scientific enquiry. There is obviously more to this novel coronavirus story.

Alternative Hypothesis

Finally, let us consider Mill’s third principle of causation that “no other explanation accounts as well for the covariance of A & B, the postulated cause and effect” (Vogt, 2011, p. xxix). It seems strikingly odd, considering that human beings are living in a rather polluted version of planet earth in relation to the optimization of human health, that researchers are so tunnel-vision focused on inspecting our boogers to find a microscopic causal agent for the current COVID-19 disease. According to the CDC data, the cumulative excess mortality in the U.S. in 2020 has been significant. Roughly 500,000 more people died in the U.S. in 2020 in excess of forecasts pre-SARS-CoV-2 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). However, converse to what the monocausal pathogenic viral theory would predict, the U.S. did not see any excess mortality from death due to any cause until after the country was put on lockdown, until after the masses were quarantined, self-isolating, sanitizing with fervor, wearing masks, and social distancing. If there was a deadly and highly contagious virus, one would expect to see excess mortality or a surge in hospitalizations prior to public isolation measures and not after the fact. Once again, the causal connection between a virus and a pandemic of disease is suspect.

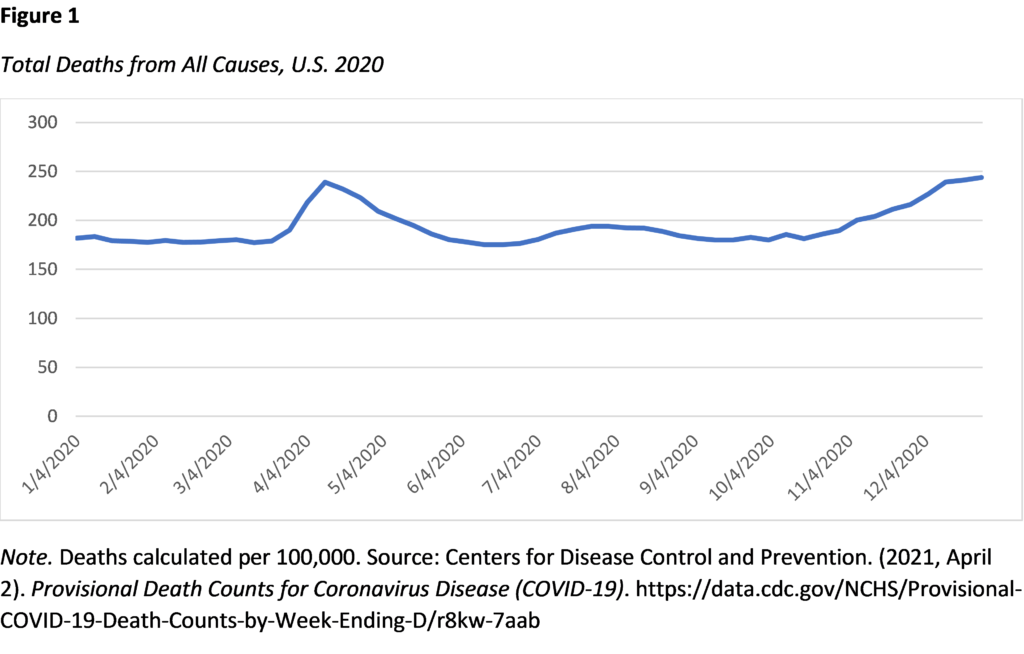

According to the CDC’s mortality data, there was no significant excess mortality in January, February, or most of March 2020 (Figure 1). The CDC mortality data does show significant excess mortality from the last week of March 2020 through the first week of June 2020 showing that more people died from all causes in April and May than the CDC forecast (Figure 1). However, if this new coronavirus has been in the U.S. since January 2020, why has the country not seen any excess mortality until April 2020 after mandatory lockdown was enforced? Why did it take three months for this supposedly highly infectious and pathogenic virus to start affecting mortality?

When scientists are faced with this glaring contradiction to the currently dominant highly pathogenic monocausal viral theory, their only response is to ignore away the contradicting data. When attempting to explain why a woman who died in early February and later tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 was not associated with an outbreak, “Dr. George Rutherford […] theorized that perhaps the woman, who worked for a company that had an office in Wuhan, was one of only a small number of people who contracted the virus at that time and that transmissions probably petered out for some reason. Otherwise, he said, the region would have seen a much bigger outbreak.” (Baker 2021). Perhaps transmission of the supposed highly infectious virus “petered out for some reason,” or perhaps the more logical conclusion is that the monocausal viral theory of contagion is not entirely accurate.

With just a two-week incubation period, certainly we should have seen small spikes in mortality by February or March of 2020. More importantly, why was there no statistically significant increase in mortality until after the government locked its citizens in their homes, shut them off from their friends and extended family, eliminated their ability to recreate, earn a living, and worship, and the mainstream media unleashed a most ruthless fear-mongering campaign upon the public? The increase in mortality during the months of April and May resulted in real-life trauma for front line, health care workers who struggled to prevent this spike in mortality and families who ultimately lost loved ones and still warrants an explanation. Alternative theories must be fleshed out, grounded in the current literature, and formed into testable hypotheses. The one glaringly obvious elephant in the room that science has a responsibility to explain away is the effect of the mainstream media’s stress-inducing fear-mongering campaign surrounding the supposed highly infectious and pathogenic SARS-CoV-2 virus. If the mainstream hypothesis is to withstand scrutiny, the very real negative health effects of unprecedented fear, anxiety, and stress must be accounted for (i.e., controlled for) before anything viral in nature may claim the entire causal inference on illness and mortality.

Psychological Impact Hypothesis

Psychologists have long theorized that a person’s mental state may have an impact on their physical health. In the last decade alone, many studies have shown that perceived stress leads to an increase in mortality (Prior et al., 2017; Malik et al., 2020). Moreover, the positive impact of perceived stress on mortality is greater for persons with pre-existing conditions. While the following may seem self-evident, a psychological survey study in China showed that 35 percent of respondents showed signs of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Qiu et al., 2020). In Italy a study found that 67.3 percent, 81.3 percent, and 72.8 percent of respondents were suffering from depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively (Mazza et al., 2020). Moreover, psychological distress in the wake of previous pandemics and episodes of government lockdowns, namely in China, has been well documented (Torales et al., 2020). The psychological impact of the media’s fear mongering campaign and the lockdowns in the U.S. and the U.K. is quickly coming into focus (Sher, 2020; Daly & Robinson, 2021). According to Kumar and Nayar (2020), “[The WHO] speculates that new measures such as self-isolation and quarantine […] may lead to an increase in loneliness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, harmful alcohol, and drug use, and self-harm or suicidal behavior” (p. 1). It is very likely that psychological distress from the corporate media’s monumental fear mongering campaign accounts for at least a portion of the excess mortality seen in the U.S. in 2020 and not a viral contagion.

Psychologists have also modeled and documented the impact of economic recession or depression on the unemployment rate and subsequent suicide rate. Brenner (1976) attempted to quantify the impact of unemployment on deaths of despair. A more recent study estimates that an increase in worldwide unemployment from 4.94% to 5.64% “would be associated with an increase in suicides of about 9570 per year. In the low scenario, the unemployment would increase to 5.088%, associated with an increase of about 2135 suicides” (Kawohl & Nordt, 2020). While these are global estimates, it is clear that an increase in unemployment in the U.S. due to the shutdowns will have a positive and measurable impact on deaths of despair. According to Roelfs et al. (2011), being unemployed increased one’s risk of death by 63 percent relative to employed persons. Moreover, Brenner and Bhugra (2020) found that “economic damage caused by decline in national income and wealth has an especially powerful damaging effect on elevating male suicides in early middle age” with similar effects on females. Since it is known that psychological and economic distress have negative effects on human health and can increase mortality, some portion of the excess mortality experienced during 2020 in the U.S. must be attributable to psychological phenomena and not the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Let us consider a few different scenarios concerning the impact of mental health on mortality during 2020 in the U.S. Consider the scenario where 35 percent, as in the China study, of the most vulnerable age groups, U.S. adults aged 45 years and older, suffered from psychological distress during the year, 2020. There were roughly 137.9 million Americans aged 45 years and older in the U.S. in 2020 (United States Census Bureau, 2020). Thirty five percent yields roughly 48.269 million Americans that were likely suffering from psychological distress. If just 1 percent sought hospital care with COVID-19-like symptoms, that would yield 482,692 hospital visits attributable to a psychological cause. With a 21 percent in-hospital mortality rate during the peak of mortality (Bean, 2021), that would yield 101,365 deaths attributable to the mass media’s fear mongering campaign, not a viral infection. According to CDC data, there were 496,827 excess deaths in the U.S. in 2020, and 361,891 were associated with the COVID-19 disease (CDC, 2021). That is, roughly 20 to 28 percent of excess mortality in the U.S. in 2020 could be attributable to the mass media’s fear mongering campaign and the government’s draconian lockdown measures.

As the current pandemic’s negative affect on mental health has already been documented, along with historical evidence from previous pandemics, and the causal connection between perceived stress and increased mortality has been documented, it is reasonable to expect a causal relationship between the mainstream media’s negative impact on the U.S. population’s mental health and an increase in mortality. Psychological distress (i.e., fear, anxiety, depression) as a confounding variable must be accounted for in any attempt to tease out a causal connection between a supposed infectious and pathogenic virus and an increase in mortality.

It is necessary to explore an alternative theoretical model that may explain the significant causal connection between the unprecedented fear Americans experienced in 2020 and the increased mortality in the U.S. in 2020.

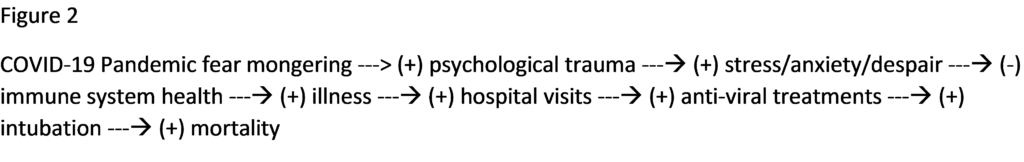

The model presented in Figure 2 posits that the media’s monumental fear mongering campaign increased the amount of psychological trauma experienced by Americans in 2020. This led to increased levels of stress, anxiety and depression, as psychologists found in China and Italy during the peak of 2020’s hysteria (Qiu et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020). Increased stress and anxiety are known to decrease immune health which subsequently increases rates of illness, as evidenced by countless studies, including studies on the stress and anxiety-mortality connection (Prior et al., 2017; Malik et al., 2020). Increased rates of illness would lead to an increase in hospital visits, as most urgent care and doctor’s offices were closed to in-person visits through 2020; sick persons were directed to hospitals instead. In hospitals front-line healthcare workers were instructed to follow the WHO’s guidelines for treatment and patients were experimented on with highly toxic anti-viral drugs and rushed to intubation (World Health Organization, 2020). The experimental treatment program designated by the WHO produced at least a 21 percent mortality rate during the peak of the so-called pandemic (Bean, 2021). This model may explain roughly 20 percent of the excess mortality experienced in the U.S. in 2020.

Nursing Home Impact

Nursing homes are home to the most vulnerable groups due to both residents’ age and pre-existing conditions. Insert an unprecedented onslaught of fear, stress, and anxiety from the mainstream media’s fear mongering and couple that with the extreme isolation due to quarantine and the elimination of visitors, and you would be left with a gloomy outlook for survival. To exacerbate the matter further, there is evidence that the quality of care suffered at several nursing homes during the so-called pandemic due to staffing shortages that were also directly attributed to the so-called pandemic (Fallon et al., 2020). The most vulnerable groups of Americans were left isolated, afraid, alone, and improperly cared for which contributed to the excess mortality in the U.S. in 2020, not SARS-CoV-2.

Nursing homes became a significant source of mortality in the U.S. in 2020. “According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, states reported […] almost 44,000 deaths in nursing homes, assisted living, and other aging care facilities by early June, representing at least 40% of total US deaths. And in 26 states, at least 50% of COVID-19 deaths were in long-term care facilities as of May 28” (Garnett & Grabowski, 2020). We now know that the total number of nursing home deaths in 2020 comprise a significant portion of overall mortality in the U.S. in 2020. At least roughly 174,000 COVID-19 deaths amongst the oldest age groups in the U.S. in 2020 occurred in nursing homes (Conlen et al., 2021), and there is evidence that this figure is under reported (Hogberg, 2021).

The U.S. had roughly 496,827 more deaths than were forecast in 2020 that require an explanation. Thirty five percent of those deaths occurred in nursing homes amongst the oldest and most vulnerable citizens. If an additional number of deaths, say 101,365, could be attributed to the media’s excessive fear-mongering campaign, approximately 55 percent of the excess mortality witnessed in 2020 would not be attributable to a deadly virus. That would leave roughly 221,462 excess deaths to be explained by a viral contagion responsible for the suspension of American’s civil liberties, the destruction of small businesses and local economies, an enormous wave of mental health disorders, a widely opened gateway for government overreach, the restructuring of the civilian process for accessing airline travel, and the furtherment of the pharmaceutical industry’s mandatory vaccine agenda.

It is necessary to explore an alternative theoretical model that may explain the significant causal connection between the lack of proper care, the onslaught of fear, and the isolation of America’s most vulnerable citizens, those in nursing homes or long-term care facilities, and the increased mortality in the U.S. in 2020.

The model presented in Figure 3 posits that fear, stress, anxiety, despair from isolation, and improper care may be responsible for the excess nursing home deaths that occurred in the U.S. in 2020, not SARS-CoV-2. The media’s fear mongering campaign led to an increase in psychological distress amongst nursing home residents that was exacerbated by unprecedented isolation. This likely led to an increase in depression which was exacerbated by the lack of proper care which led to a significant increase in mortality.

Concluding Remarks

The scientific community has a responsibility to investigate alternative causes to explain the excess mortality that occurred in the U.S. in 2020. Given the unprecedented changes to human behavior that occurred as a result of government restrictions and the psychological stress that followed, it is prudent that these confounding factors be examined more thoroughly to better inform future reactions to similar naked-eye invisible threats such as pathogenic viruses. The scientific community concluded the monocausal viral theory sufficiently explained a cluster of forty-one patients in Wuhan, China who were suffering from a seemingly unique disease. No other alternative causes have yet to be sufficiently examined to explain the cluster of patients in Wuhan or the excess hospitalizations or mortality experienced in certain countries around the world. A myriad of confounding variables, including psychological trauma, improper or experimental treatment, exposure to environmental toxins, or individual lifestyle and dietary decisions, need to be explained away in order to accurately quantify the excess hospitalizations and mortality experienced in 2020 that may be attributed to a viral contagion.

REFERENCES

- Anthony, S.J., Epstein, J.H., Murray, K.A., Navarrete-Macias, I., Zambrana-Torrelio, C.M., Solovyov, A., Ojeda-Flores, R., Arrigo, N.C., Islam, A., Ali Khan, S., Hosseini, P., Bogich, T.L., Olival, K.J., Sanchez-Leon, M.D., Karesh, W.B., Goldstein, T., Luby, S.P., Morse, S.S., Mazet, J., Daszak, P., & Lipkin, W.I. (2013). A Strategy To Estimate Unknown Viral Diversity in Mammals. American Society for Biology, 4(5), DOI: 10.1128/mBio.00598-13.

- Baker, Mike. (2021, May 15). When Did the Coronavirus Arrive in the U.S.? Here’s a Review of the Evidence. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/us/coronavirus-first-case-snohomish-antibodies.html

- Barnett, M.L., & Grabowski, D.C. (2020, March 24). Nursing Homes Are Ground Zero for COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0369

- Bean, M. (2021, March 9). In-hospital COVID-19 death rate fell significantly last year, study finds. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/patient-safety-outcomes/in-hospital-covid-19-death-rate-fell-significantly-last-year-study-finds.html

- Brenner, H. (1976). Estimating the Social Costs of National Economic Policy: Implications for Mental and Physical Health, and Criminal Aggression. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Brenner, M.H., & Bhugra, D. (2020). Acceleration of Anxiety, Depression, and Suicide: Secondary Effects of Economic Disruption Related to COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1422. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.592467

- Campbell, D. T., Chelimsky, E., Shadish, W. R., SHADISH, W., & Cook, T. D. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). United States Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Provisional COVID-19 Death Counts by Week Ending Date and State. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from https://data.cdc.gov/browse?category=NCHS&sortBy=last_modified

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). What Are the Risk Factors for Lung Cancer? Retrieved March 31, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/risk_factors.htm#:~:text=People%20who%20smoke%20cigarettes%20are,the%20risk%20of%20lung%20cancer.

- Chavarria-Miró, G., Anfruns-Estrada, E., Guix, S., Paraira, M., Galofré, B., Sáanchez, G., Pintó, R., & Bosch, A. (2020). Sentinel surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater anticipates the occurrence of COVID-19 cases. COVID-19 SARS-CoV-2 preprints from medRxiv and bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.13.20129627

- Conlen, M., Ivory, D., Yourish, K., Rebecca Lai, K.K., Hassan, A., Calderone, J., Smith, M., Lemonides, A., Allen, J., Blair, S., Burakoff, M., Cahalan, S., Cassel, Z., Craig, M., De Jesus, Y., Dupré, B., Facciola, T., Fortis, B., Gorenflo, G. … & Harvey, B. (2021, March 31). One-Third of U.S. Coronavirus Deaths Are Linked to Nursing Homes. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-nursing-homes.html

- Coronavirus Existed Everywhere Before Emerging in China, Says Oxford Expert. (2020, July 6). Yahoo!News. https://in.news.yahoo.com/coronavirus-existed-everywhere-emerging-china-064200844.html?soc_src=social-sh&soc_trk=fb

- Daly, M., & Robinson, E. (2021). Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 603-609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.035.

- Fallon, A., Dukelow, T., Kennelly, S.P., & O’Neill, D. (2020). COVID-19 in nursing homes. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(6), 391–392. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa136

- Hogberg, D. (2021, March 21). Biden HHS nominee under pressure over missing nursing home COVID-19 death data. Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/levine-nomination-missing-nursing-home-data

- Kawohl, W., & Nordt, C. (2020). COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. The Lancet: Psychiatry, 7(5), 389-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30141-3

- Kumar, A. & Nayar, K.R. (2020): COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1757052

- La Rosa, G., Mancini, P., Ferraro, G.B., Veneri, C., Iaconelli, M., Bonadonna, L., Lucentini, L., & Suffredini, E. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating in northern Italy since December 2019: Evidence from environmental monitoring. Science of The Total Environment, 750(141711). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141711.E.

- Malik, A.O., Peri-Okonny, P., Gosch, K., Thomas, M., Mena, C., Hiatt, W.R., Jones, P.G., Provance, J.B., Labrosciano, C., Jelani, Q., Spertus, J.A., & Smolderen, K.G. (2020). Association of Perceived Stress Levels With Long-term Mortality in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease. JAMA Network Open, 3(6). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8741

- Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093165

- Moxon, E. R., Smith, A.L., Averill, D.R., & Smith, D. H. (1974). Haemophilus influenzae Meningitis in Infant Rats after Intranasal Inoculation. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 129(2), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/129.2.154

- National Research Council. (2002). Scientific Research in Education. Committee on Scientific Principles for Education Research. Shavelson, R.J. and Towne, L. Editors. Center for Education. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Neilson, S., & Woodward, A. (2020, May 22). A comprehensive timeline of the new coronavirus pandemic, from China’s first case to the present. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.nl/coronavirus-pandemic-timeline-history-major-events-2020-3?international=true&r=US

- Prior, A., Fenger-Grøn, M., Larsen, K.K., Larsen, F.B., Robinson, K.M., Marie Nielsen, M.G., Christensen, K.S., Mercer, S.W., & Vestergaard, M. (2016). The Association Between Perceived Stress and Mortality Among People With Multimorbidity: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 184(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv324

- Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General psychiatry, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

- Ridge, C. A., McErlean, A. M., & Ginsberg, M. S. (2013). Epidemiology of lung cancer. Seminars in interventional radiology, 30(2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1342949

- Roelfs, D.J., Shor, E., Davidson, K.W., & Schwartz, J.E. (2011). Losing life and livelihood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.005.

- Sher, L. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(10), 707–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202

- The COVID Tracking Project. (2021, March 7). Totals for the US. https://covidtracking.com/data/national

- Torales, J., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212

- United States Census Bureau. (2020, December 14). National Demographic Analysis Tables: 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/popest/2020-demographic-analysis-tables.html

- Vogt, Paul. 2011. Sage Quantitative Research Methods. Vol 1-4.. SAGE Publications.

- World Health Organization. (2020, May 27). Clinical Management of COVID-19. WHO reference number: WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.